How did Irish nationalists historically conceive of Irish identity?

Recently, Micheál Martin, the Irish Tánaiste and leader of Fianna Fáil, uploaded a speech delivered to the Dáil on his conception of Irish nationalism. Martin wrote that:

The people who fought for and founded our state saw it as a place with multiple identities, open to the world and embodying the most important republican principle of all, to reflect the diversity of its people.

In the speech itself, Martin warned against:

Those who want to seal Ireland off from the world, those who aspire to some mythical purity on this island, know nothing of our past and have nothing to offer a country whose progress and prosperity is fundamentally based on its diversity and engagement with the world.

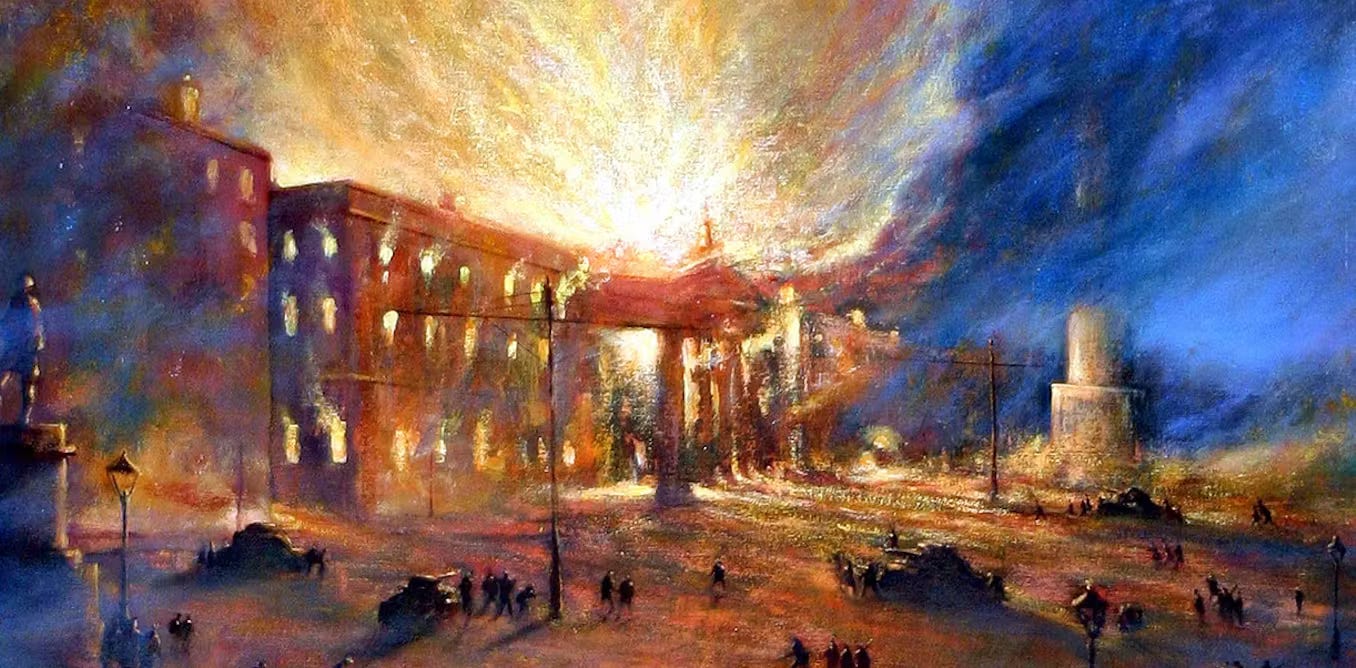

The statements by Martin follow a pattern of regime politicians, intellectuals and journalists rewriting Irish history. The Irish nationalist struggle, and thus the founding of the nation, is being revised away from an ethnonationalist struggle for independence — the “Ireland Gaelic and free” envisioned by Pádraig Pearse.

Instead, seemingly left-wing or egalitarian elements of the nationalist revolution are emphasised: the proclamation addressed “Irish men and Irish women”, so it was really all about feminism and pluralism. Figures like James Connolly, a militant Marxist, are amplified, while the blood and soil ideology that informed the majority of leaders and participants in the revolution is ignored.

A typical example of this kind of revisionism was published in History Ireland, in an essay titled Take it down from the mast, ‘Irish patriots’. The author wrote that

The emerging alt-right are increasingly desperate to assert their claim to the historic legacy of the 1916 Rising, the reality is that the ideology of Irish republicanism has always espoused a much more open, liberal and secular concept of Irish citizenship then they are aware of or willing to admit.

The true inheritors of Irish Republicanism, in the view of this author, are the multiculturalists. After all, the revolution counted among its members many returning political exiles from England and the continent, and some of its most important members, like James Connolly, were even born in foreign countries like Scotland. A quote is given from Wolfe Tone, the founder of Irish Republicanism, which is supposed to be a repudiation of Irish ethnic identity

Tone’s definition of Irishness was based not on blood or creed. He sought ‘To unite the whole people of Ireland, to abolish all past dissentions and substitute the name of Irishman in the place of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter …’.

Of course, it’s very evident from the quote provided that Tone is talking about the Irish people putting aside religious differences which divided them. If he didn’t see a difference between this Irish people and the British people (or any other people), why would he have even bothered pushing for Irish national independence, let alone dying for it?

The New Nationalism

This kind of sloppy scholarship is becoming increasingly popular as champions of diversity look to remake Ireland’s revolutionary history in their image.

The Irish revolution is no longer the struggle of a distinct race striking for independence from rule by foreigners, but is now part of a more universal story of the struggle against imperialism, racism and tyranny. This recasts the Irish struggle as one of many anti-colonial uprisings in the 20th Century. Our comrades are the Algerians, the Mau Mau and Nelson Mandella.

More importantly, by adopting the values of the left and challenging white supremacy, racism and heteronormativity, we are somehow carrying on the struggle of Pearse, Connolly and Collins. But now, this struggle is shared by our ruling parties, mainstream media, Blackrock and the big American corporations headquartered in Dublin, and immigrants who know little to nothing of Irish history.

This identification of Irish nationalism as a vaguely leftist, “anti-racist” struggle has also been taken up by some members of the Anglosphere right. Sinn Féin leadership kneeling in honour of the Black Lives Matter movement, they argue, is par for course for the Irish nationalist cause, which was always based on a “slave morality” resentment against high civilisation, embodied in the British Empire.

Alongside this revision, there has also begun this bizarre trend of Irish leftists claiming that Irish nationalists who have an ethnic conception of nationhood are somehow importing foreign ideas. Ethnic nationalism and opposition to diversity they claim, is more akin to British nationalism, represented by people like Tommy Robinson and Nick Griffin. They have even taken to promoting elaborate conspiracy theories about those who promote “Ireland for the Irish” being somehow controlled by shadowy British forces. Absurd as this may sound on its face, this has actually become the dominant narrative for the Irish left opposed to nationalism.

This kind of revision isn’t unique to the left, either. Recently, John McGuirk, the editor of the popular conservative news site Gript, turned his hand to deconstructing ethnonationalism. McGuirk’s article, “hardline ethnonationalism is an intellectual dead end”, was sparked by his outrage at Irish ethnonationalists claiming Rhasidat Adeleke, an ethnically Nigerian sprinter now representing Ireland, is not in fact Irish. McGuirk treats the ethnonationalist view of identity as something very new, fringe and radical, belonging only to “tens of dozens” who make a lot of noise on social media.

So how accurate is this story? Did Irish nationalists view their struggle as part of a broader insurrection of the coloured masses against white global dominance? Did they think Irishness was a civic identity, which could be extended to African sprinters and Polynesian rugby players, as McGuirk argues? We don’t need to speculate.

John Mitchel on race

Before the Easter Rising in 1916 launched the national revolution that would win Irish independence, the nationalist struggle was led by Fenians like John Mitchel. Mitchel led the Young Ireland movement, and as editor of The Nation and the United Irishmen, he became one of the most influential spokesmen for Irish nationalism in the 19th Century. Pearse called Mitchel’s jail journal “the last of the four gospels of the new testament of Irish nationality”.1

Mitchel is a controversial figure today, for while in exile in America at the outbreak of its Civil War, he became a staunch supporter of the Confederacy. Mitchel was influenced by the reactionary historian Thomas Carlyle, and shared his opposition to Black and Jewish emancipation. In fact, he wrote defences of slavery, and advocated a return of the Atlantic slave trade. Two of Mitchel’s sons enlisted in the Confederate army, with one dying at the battle of Gettysburg.

Therefore, as the war approached its end, Mitchel was appalled at proposals in the Confederacy to enlist slaves to fight in exchange for their freedom. He wrote:

“If it be true that the state of slavery keeps these people depressed below the condition to which they could develop their nature, their intelligence, and their capacity for enjoyment, and what we call “progress”, then every hour of their bondage for generations is a black stain on the white race.2

Mitchel’s uncompromising defence of slavery was controversial in his own time, but he remained committed even after the defeat of the Confederacy and his return to Ireland. Mitchel once said the following in response to a hypothetical of a freed Ireland having slaves of its own:

What do you think of Ireland’s emancipation now? Would you like an Irish Republic with an accompaniment of slave plantations?”—just answer quite simply—Yes, very much. At least I would answer so.3

How anomalous was Mitchel’s view? Well, Arthur Griffith was the founder of the original Sinn Féin, and obviously an enormously important figure in the story of Irish nationalism. He wrote in 1913, in defence of Mitchel that:

The right of the Irish to political independence never was, is not, and never can be dependent upon the admission of equal right in all other peoples.

….

Even his views on negro-slavery have been deprecatingly excused, as if excuse were needed for an Irish Nationalist declining to hold the negro his peer in right. When the Irish Nation needs explanation or apology for John Mitchel the Irish Nation will need its shroud.4

Griffith, Casement & The Crime Against Europe

While editor of the newspaper Nationality, Griffith called the entry of non-whites into Europe “the crime against Europe”, expressing views of these races which would certainly have him classified today as a white supremacist, and using this to attack the Allied powers:

The nations who introduced into a European war these Asiatic and African savages…will stand condemned at the bar of posterity for the worst act ever committed by white men against the white race.

…

Europe…is the white man’s land, and the introduction of savage Asiatics and Africans into Europe in war between civilised Powers is unparalleled in European history since anno domini. It is a betrayal of the white race, and an infamy pregnant with a grim and horrible danger and woe in the future.5

What would Griffith think of the Sinn Féin of today, who support a “Republic for all” and remain supportive of immigration in a country where over a fifth of the population are now foreign born? Well, in 1913 Griffith already believed there were too many foreigners in Ireland:

Two-and-a-half per cent of our population is of foreign birth—mostly English—too great a percentage for a country like ours.6.

It’s interesting now to read Griffith, a figure so identified with the Irish cause, bringing his nationalist perspective to the Great War. But he was not the only Irish revolutionary to turn his attention to the great geopolitical shocks of the early 20th Century and how they concerned Ireland. And this engagement with European and world affairs reveals much about how these figures thought about broader racial questions.

Roger Casement was an Irish revolutionary and British civil servant who was executed for his role in the 1916 Easter Rising, just five years after being given a knighthood by the British state. Casement wrote a series of very prescient articles about the prospect of a great European war in the years leading up to the outbreak of World War I. As well as being from the perspective of someone in favour of Irish independence, Casement also expresses a broader concern about the geopolitical direction of Europe — namely that the British Empire was strengthening non-European races in their drive for hegemony over the continent. Casement wrote of how the British Empire strengthened the “Asiatic race” at the expense of Europeans:

The neutrality of Belgium never became a war issue until war had long since been decided on and had actually broken out; while Japan came into the contest solely because Europe had obligingly provided one, and because one European power preferred, for its own ends, to strengthen an Asiatic race to seeing a kindred white people it feared grow stronger in the sun.7

Casement also lamented the twisted circumstance of the British Empire appealing to Germanic and Irish Americans to aid them in subduing their own ethnic kin in Europe. Casement actually framed the struggle against the British Empire as an existential struggle for the future of the white race:

Arrangements with England, detentes, understandings, call them what you will, are merely parleys before the fight. The assault must be delivered, the fortress carried, or else Germany and with her, Europe, must resign the mission of the white races and hand over the government and future of the world to one chosen people.8

In later articles, Casement warned against the grave threat of an “Anglo-Saxon Alliance” between the British Empire and the United States, which he wrote would be a “perpetual threat to the peoples of Europe” . He proposed instead an alliance between Germany and the US as the ideal way to secure the long-term interests of white people, with a free Ireland as the link between Europe and North America. Casement was an Irish nationalist, yet he framed the struggle for Irish freedom as accommodating a more secure and prosperous world for the broader European race.

“Elementary principles of governing white men”

Similar appeals were made at the close of the First World War, as Irish representatives highlighted the indecency of a European nation existing in a state of subjugation.

The Irish representative at the 1919 Versailles conference, Seán T O’Kelly, failed to secure a meeting with US President Woodrow Wilson. In his frustration, O’Kelly remarked to an American journalist that “It seems that the blacks and yellows, all colours and races, may be heard before the conference except the Irish.”

A year later, O’Kelly sent a letter seeking an audience with Pope Benedict XV. O’Kelly wrote that Sinn Féin’s aim was “to obtain that independence which every other white race in the world has already won.”

Éamon De Valera, the President of the Irish Republic during the War of Independence, spent much of the war fundraising in the United States. On one occasion — in Birmingham, Alabama — he appealed to his American audience by reminding them that Ireland “was the only white nation on earth still in the bonds of political slavery”.

Erskine Childers, another prominent member of the Irish revolution, started out sympathetic to the British Empire before coming to take up the Irish struggle. He wrote against British imperialism in Ireland not from a universal opposition to imperialism, but because of what he called the “elementary principles of governing white men”. Childers had first come to support the Boer struggle for independence before the Irish, and he asserted that:

No white community of pride and spirit would willingly tolerate the grotesque form of Crown Colony administration, founded on force, and now tempered by a kind of paternal State Socialism under which Ireland lives to-day.9

Not a universal opposition to imperialism or conquest informed Childers’ argument, but a belief that independence was a basic right of white peoples like the Irish and the Boer. Indeed, Childers contrasted colonial rule over the Irish with colonial rule over American Indians:

In America and Ireland the Colonies were bi-racial, with this all-important distinction, that in America the native race was coloured, savage, heathen, nomadic, incapable of fusion with the whites, and, in relation to the almost illimitable territory colonized, not numerous; while in Ireland the native race was white, civilized, Christian, numerous.10

In contrasting the “coloured, savage, heathen” race with the “white, civilized” Irish, Childers makes a plea for national independence which assumes racial hierarchy and does not reject imperial rule outright, instead highlighting the injustice of one white people being subject to another so ethnologically similar.

The uniqueness of the Irish race

While De Valera is the founder of the Fianna Fail party, Fine Gael has always looked to Michael Collins as its spiritual successor. Collins is seen as an altogether more moderate and pragmatic figure, having led the war against British forces in Ireland before negotiating a treaty and fighting the hardliner Republicans. Collins too, wrote of a racial conception of nationalism as it concerned the Irish struggle, believing that the unique racial characteristics of the Irish would show in their national struggle:

This is where our Irish temperament, tenacity of the past, its vivid sense of past and future greatness, readiness for personal sacrifice, belief and pride in our race, can play an unique part, if it can stand out in its intellectual and moral strength, and shake off the weaknesses which long generations of subjection and inaction have imposed upon it.11

Collins not only believed the Irish characteristics would help them win the war, but also that racial purity would maintain the legitimacy of the new nation-state, flowering into a distinct Gaelic civilization.

It was in this spirit that Aodh De Blácam, an Irish nationalist journalist and future Senator, wrote in 1918 that the Easter Rising brought:

The nation back to the attitude of 220 years ago, the normal attitude of race-consciousness. Now, as then, the nation knows itself to be the true owner of this island.12

Elsewhere, De Blácam described this national and racial consciousness which he believed had animated ancient Ireland:

The nation which had come into being in Cormac’s day was a nation comparable to antique Greece or Fascist Italy…It must have abounded with energies that it drew from an intense excitement of racial consciousness.13

I can imagine an Irish Republican detractor reading this and suggesting these are mostly the words of “free staters”, and the anti-treaty, hardline Republicans had a broader conception of Irishness. But this is not the case. For example, Ernie O’Malley, the Republican intellectual who served as assistant chief of staff of the Anti-Treaty IRA during the Irish Civil War. A historian who profiled O’Malley writes that:

Throughout his political writings he talks of race, racial qualities, racial similarities and differences… he sympathizes with the ideal of cherishing and restoring a supposedly authentic Gaelic Irish culture.14

O’Malley wrote that he opposed the pro-Treaty forces because they represented the same system which had stifled the expression of Irish nationhood prior. They would, he believed, warp “the spirit of the race” from expressing its unique “type of genius.”15

This kind of theorising about the unique racial characteristics of the Irish is also present in Pádraig Pearse, the father of the 1916 Rising and the uprising in national consciousness that resulted from it. Pearse engaged with great interest with the racial theories of his day, in one case writing in opposition to the contention that an interest in the Indo-Europeans was alien to Ireland:

The broad scientific history which shows us as a branch of the Aryan race that played a big part in early European history, and later, as a nation isolated politically from the rest of Europe, but having every interchange with outside nations which progress demanded, receiving and giving, must take the place of the date book and the agony column style of history which has taught Irishmen to hate their foes but not to love each other.16

Douglas Hyde, the first President of Ireland and the founder of the Gaelic league, which led the revival in the Irish language, also spoke of the Irish as an Aryan people, and in an 1899 lecture he said the Irish needed a return to the country’s “pure Aryan language.”

In an essay titled The Necessity for De-Anglicising Ireland, Hyde discussed the development of the Irish nation in racial terms:

In a word, we must strive to cultivate everything that is most racial, most smacking of the soil, most Gaelic, most Irish, because in spite of the little admixture of Saxon blood in the north-east corner, this island is and will ever remain Celtic at the core.. On racial lines, then, we shall best develop, following the bent of our own natures.17

Hyde believed, like Collins, that the charting of an independent course for the Irish nation would bring out the best racial characteristics of the Irish people:

Upon Irish lines alone can the Irish race once more become what it was of yore – one of the most original, artistic, literary, and charming peoples of Europe.18

In 1922, the Irish Race Congress was held in Paris. This was part of a series of “Irish Race Conventions” held in the 19th and 20th Centuries. One speaker at the Paris Congress was Hyde who told the convention that:

The Irish are neither negroes nor mongrels nor castaways, nor are they a people without a past. On the contrary, they boast almost the proudest race heritage in Europe. They are the descendants of a stock to which almost every country in Western Europe owes, and frankly acknowledges that it owes, a debt of lasting gratitude.19

The task for attendees then, Hyde argued, would be to instill the newly independent Irish with a sense of heritage and pride in their race. Writing on this speech by Hyde, where he compares the subjugation of the Irish to other colonised people, John Brannigan, a modern scholar, writes this:

It is clear from Hyde’s eagerness to distinguish the Irish as white, western Europeans that he is not making an analogy here for the sake of solidarity, but to emphasise the absurdity of the Irish being seen as anything other than white Europeans, deserving of the status afforded white Europeans over and above the rights of the various racial others Hyde mentions in his lecture.20

Brannigan’s work is interesting in showing the racial thought of many Irish leaders and intellectuals. Once such intellectual was the nobel laureate W. B. Yeats, who also became an advocate of the nationalist cause, and served as a Senator in the Irish Free State. In Yeats’s work:

There is this underlying notion of a race as a ‘Unity of Being’, as having a collective memory, or collective bank of originary symbols, images or myths…The idea of the racial community promises to circumvent the potential anomie of modern social relations.21

Yeats himself wrote that:

Race, which has for its flower the family and the individual, is wiser than Government, and it is the source of all initiative.22

The Celtic Revival and Irish racial consciousness

Both Yeats and Hyde were monumental figures in the story of Ireland’s Celtic revival. Hyde’s view that the purpose of this revival in Irish language, mythology self-consciousness was to reawaken a unique racial identity and foster its best characteristics was widely shared by other figures involved in the movement. Writing on “The Celtic Revival of Today” in 1899, Father J. O’Donovan summarised the aims of the movement as so:

The present movement means, moreover, the emancipation of the Celt from foreign racial influence, and the building up of a new art and literature in Ireland, animated by the Celtic spirit, informed by everything that is good in Ireland’s past… It aims at no slavish imitation of the past, but at the establishment of a new era, informed by the spirit of the past in so far as that spirit is racial, and, as such, true for all time.23

Similarly, a 1903 work on the importance of the revival of the Irish language recommended it on the basis that it would:

Train up the rising generation in all the traditions of their ancestors, it will keep alive those characteristics that individualize our race, it will keep alive our spirit of chivalry, of heroism, of generosity, of faith.24

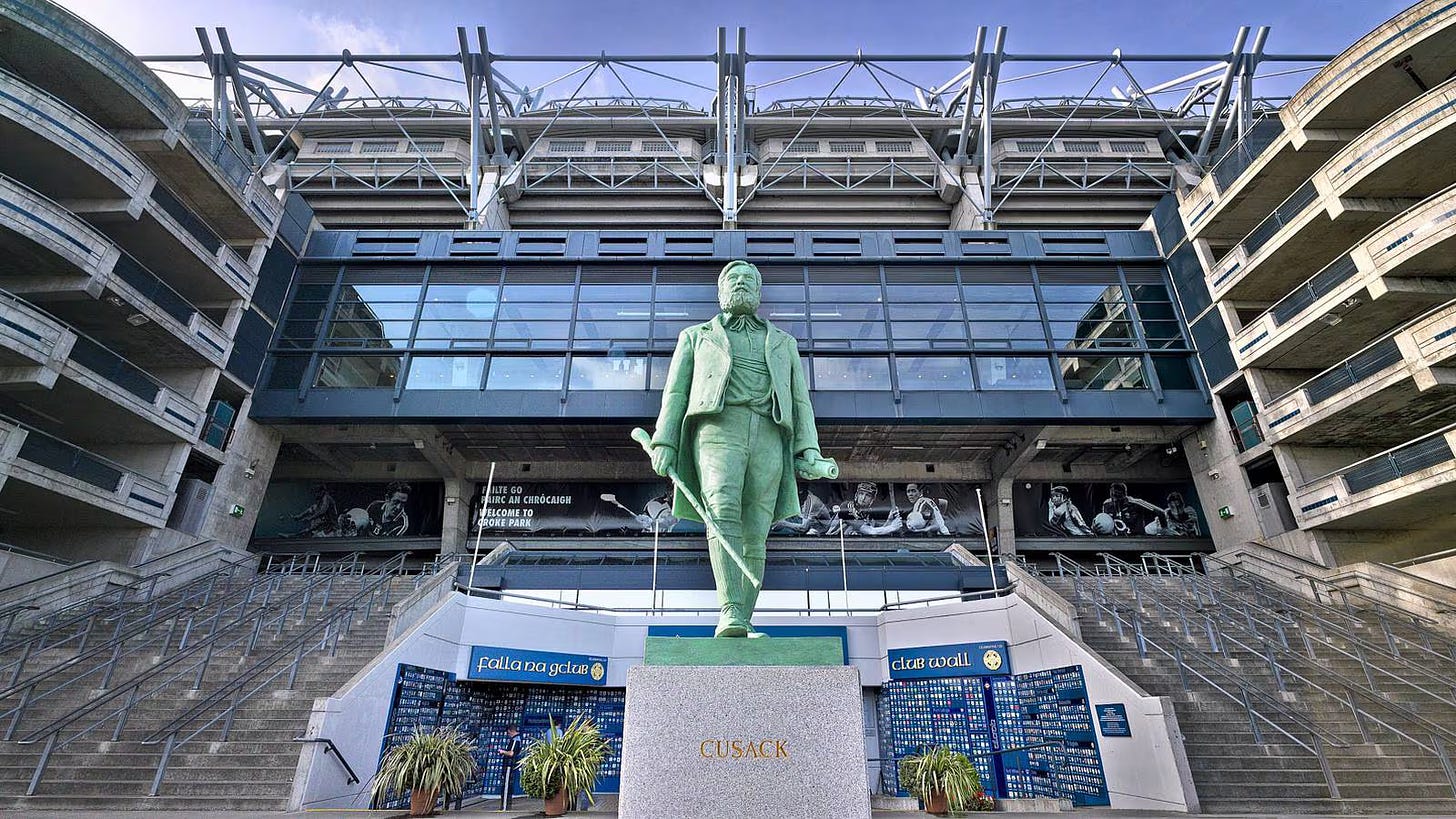

The re-awakening of Irish identity was not limited to the revival of the Irish language. The formation of the Gaelic Athletic Association in 1884 gave organisation and formal rules to the traditional Irish sports of Gaelic football and hurling, a response to the growing popularity of British sports in Ireland like rugby and cricket.

The revival of uniquely Irish sport became an important part of the broader Celtic cultural revival, and here too, the key figures were driven by ethnic nationalism and racial thinking. This was the reasoning of Michael Cusack, the founder of the GAA, writing in 1884:

The strength and energy of a race are largely dependent on the National pastimes for the development of a spirit of courage and endurance. A warlike race is ever fond of games requiring skill, strength, and staying power. The best games of such a race are never free from danger. But when a race is declining in martial spirit, no matter from what cause, the national games are neglected at first and then forgotten. And as the corrupting and degrading influences first manifest themselves in capital towns and large cities, so, too, we find that the national pastimes and racial characteristics first fade and disappear from such large centres of population.25

Cusack believed a revival in Gaelic games like hurling, “invented by the most sublimely energetic and warlike race the world has ever known”, would preserve the strength and martial spirit of the Irish. So nationalistic was Cusack that he was the basis for the character of “The Citizen” in Joyce’s Ulysses, portrayed as a fiercely nationalist anti-Semite — a portrayal representing for Joyce the “xenophobic ideologies of radical Celticists“.26

No ambiguity

A later example of the ethnic conception of the Irish nation is found in a 1938 work by Pádraig Ó Siochfhradha, another renowned Irish writer and member of the Irish Senate. Perhaps more than anyone hitherto mentioned, Ó Siochfhradha outlines precisely the ethnonationalist basis for Irish nationalism, rooted in the unity of the Irish race and their “hereditary right” to the land. He wrote that the Gaels in Ireland had the five elements or ingredients that comprise full nationality. These were:

(1) A population of a single heritage and a single blood ie. unity of race.

(2) A population with a single language- the Irish language was the only common language for the whole race.

(3) A uniformity of memory and tradition with regard to history, culture and custom.

(4) A land theirs by hereditary right.

(5) Political freedom and authority over that land, that is, a state.27

If he was more explicit than others named in outlining the ethnonationalist basis for Irish nationalism, it was only because many of these precepts were taken for granted, too obvious to any Irishman to need theorising.

If the common use of the word “race” among these writers to denote an ethnic group like the Irish has seemed confusing, that’s because our sharp distinctions between race, ethnicity and nation are quite modern. The distinction between “civic” and “ethnic” nationalism was not coined until 1944, with the publication of Hans Kohn’s The Idea of Nationalism.

Prior to a move away from racial thought after the Second World War and the popularisation of the less biologically reductionist term of “ethnicity”, race had been used to denote individual ethnic groups as well as the larger racial groups we recognise today. Hence, it was common to refer to the Irish race, the French race or the English race. This is only controversial today due to the political push to decouple ethnicity from biological kinship.

All the men surveyed here — revolutionaries, politicians, diplomats and poets — had an ethnic, racial conception of Irishness. They did not view the Irish struggle as anything but the struggle of a race — a subrace of the white, European race — for independence. They maintained a sense of racial identification with a broader white or Aryan race, and in the case of men like Casement and Griffith, expressed thoughtful arguments on the interests of this race and the Irish place within it.

No one would reject more strongly the de-nationalising project of the modern parties still carrying their lineage, and the recasting of their struggle as one that welcomed ethnic and racial diversity, than these men themselves. Rewriting their struggle to be for anything but an ethnonationalist cause is not only insulting to the intelligence of anyone with the most basic knowledge of Irish history, but a desecration of the great legacies of these men and of anyone who has sacrificed for the cause of Irish freedom.

John Mitchel: “Flawed Hero.” History Ireland, 2013. https://www.historyireland.com/john-mitchel-flawed-hero

John Mitchel: “Flawed Hero.” History Ireland, 2013. https://www.historyireland.com/john-mitchel-flawed-hero

John Mitchel: “Flawed Hero.” History Ireland, 2013. https://www.historyireland.com/john-mitchel-flawed-hero

Donnelly, Seán. “Revolution and Nationalism in Treatyite Political Thought, 1891–1924.” Irish Historical Studies 47, no. 171 (2023): 130–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/ihs.2023.8.

Griffith, Arthur. “Nationality”, 30 October 1915.

Griffith, Arthur. “The Census.” Sinn Féin, April 26, 1913. Republished in “An Cartlann.” Accessed June 22, 2024. https://cartlann.org/authors/arthur-griffith/the-census/

Casement, Roger. The Crime Against Europe: The Writings and Poetry of Roger Casement. 1915.

Casement, Roger. The Crime Against Europe: The Writings and Poetry of Roger Casement. 1915.

Peatling, G. K. “The Whiteness of Ireland Under and After the Union.” Journal of British Studies 44, no. 1 (2005): 115–33. https://doi.org/10.1086/424982.

Peatling, G. K. “The Whiteness of Ireland Under and After the Union.” Journal of British Studies 44, no. 1 (2005): 115–33. https://doi.org/10.1086/424982.

Collins, Michael, and Tim Pat Coogan. The path to freedom. Dublin: Talbot Press, 1922.

De Blácam, Aodh. Towards the Republic: A Study of New Ireland’s Social and Political Aims. Dublin: T. Kiersey. 1919.

De Blácem, Aodh Sandrach. Gaelic Literature Surveyed... Phoenix Publishing Company Limited, 1933.

English, Richard. Ernie O’Malley: IRA Intellectual. Clarendon Press, 1998

O’Malley, Ernie. The singing flame. Mercier Press Ltd, 2012

Padraig Pearse, “A Matter Of Education,” From An Claidheamh Soluis, July 24, 1909.

Hyde, Douglas, and Joseph Theodoor Leerssen. The necessity for de-Anglicising Ireland. Academic Press Leiden, 1994.

Hyde, Douglas, and Joseph Theodoor Leerssen. The necessity for de-Anglicising Ireland. Academic Press Leiden, 1994.

Quoted in Brannigan, John. Race in Modern Irish Literature and Culture. Edinburgh University Press, 2020. Pg. 42.

Brannigan, John. Race in Modern Irish Literature and Culture. Edinburgh University Press, 2020. Pg. 43.

Brannigan, John. Race in Modern Irish Literature and Culture. Edinburgh University Press, 2020. Pg. 28.

Weng, Julie McCormick. “W. B. Yeats, the Irish Free State, and the Rhetoric of Race Suicide.” Chapter. In Race in Irish Literature and Culture, edited by Malcolm Sen and Julie McCormick Weng, 143–71. Cambridge Themes in Irish Literature and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024.

O’Donovan, J. (Fr.). The Celtic Revival of Today. The Irish Ecclesiastical Record, Volume 5. Dublin: Browne and Nolan [etc.]. 1899.

Ó Duinnín, Pádraig. The Preservation of the Living Irish Language: A Work of National Importance, 1903

Cusack, Michael. 1884. “A Word About Irish Athletics.” Republished in “An Cartlann.” Accessed June 22, 2024. https://cartlann.org/authors/michael-cusack/a-word-about-irish-athletics/

Cheng, Vincent J. Joyce, race, and empire. No. 3. Cambridge University Press, 1995. Pg. 198.

Ó Siochfhradha, Pádraig. Bonaventura. 1938.

Subscribe to Keith Woods

Political and social commentary, philosophy, and the occasional book club.

Categories: Geopolitics, History and Historiography, Race and Ethnicity